About the CoMSES Model Library more info

Our mission is to help computational modelers at all levels engage in the establishment and adoption of community standards and good practices for developing and sharing computational models. Model authors can freely publish their model source code in the Computational Model Library alongside narrative documentation, open science metadata, and other emerging open science norms that facilitate software citation, reproducibility, interoperability, and reuse. Model authors can also request peer review of their computational models to receive a DOI.

All users of models published in the library must cite model authors when they use and benefit from their code.

Please check out our model publishing tutorial and contact us if you have any questions or concerns about publishing your model(s) in the Computational Model Library.

We also maintain a curated database of over 7500 publications of agent-based and individual based models with additional detailed metadata on availability of code and bibliometric information on the landscape of ABM/IBM publications that we welcome you to explore.

Displaying 10 of 36 results for 'Blanca Rosa Cases Gutiérrez'

VIDA: A simulation model of domestic VIolence in times of social DistAncing

B Furtado | Published Monday, January 11, 2021Violence against women occurs predominantly in the family and domestic context. The COVID-19 pandemic led Brazil to recommend and, at times, impose social distancing, with the partial closure of economic activities, schools, and restrictions on events and public services. Preliminary evidence shows that intense co- existence increases domestic violence, while social distancing measures may have prevented access to public services and networks, information, and help. We propose an agent-based model (ABM), called VIDA, to illustrate and examine multi-causal factors that influence events that generate violence. A central part of the model is the multi-causal stress indicator, created as a probability trigger of domestic violence occurring within the family environment. Two experimental design tests were performed: (a) absence or presence of the deterrence system of domestic violence against women and measures to increase social distancing. VIDA presents comparative results for metropolitan regions and neighbourhoods considered in the experiments. Results suggest that social distancing measures, particularly those encouraging staying at home, may have increased domestic violence against women by about 10%. VIDA suggests further that more populated areas have comparatively fewer cases per hundred thousand women than less populous capitals or rural areas of urban concentrations. This paper contributes to the literature by formalising, to the best of our knowledge, the first model of domestic violence through agent-based modelling, using empirical detailed socioeconomic, demographic, educational, gender, and race data at the intraurban level (census sectors).

Peer reviewed BAM: The Bottom-up Adaptive Macroeconomics Model

Alejandro Platas López Alejandro Guerra-Hernández | Published Tuesday, January 14, 2020 | Last modified Sunday, July 26, 2020Overview

Purpose

Modeling an economy with stable macro signals, that works as a benchmark for studying the effects of the agent activities, e.g. extortion, at the service of the elaboration of public policies..

…

Peer reviewed FishMob: Interactions between fisher mobility and spatial resource heterogeneity

Emilie Lindkvist | Published Wednesday, October 16, 2019 | Last modified Tuesday, June 23, 2020Migration or other long-distance movement into other regions is a common strategy of fishers and fishworkers living and working on the coast to adapt to environmental change. This model attempts to understand the general dynamics of fisher mobility for over larger spatial scales. The model can be used for investigating the complex interplay that exists between mobility and fish stock heterogeneity across regions, and the associated outcomes of mobility at the system level.

The model design informed by the example of small-scale fisheries in the Gulf of California, Mexico but implements theoretical and stylized facts and can as such be used for different archetypical cases. Our methodological approach for designing the model aims to account for the complex causation, emergence and interdependencies in small-scale fisheries to explain the phenomenon of sequential overexploitation, i.e., overexploiting one resource after another. The model is intended to be used as a virtual laboratory to investigate when and how different levels of mobile fishers affect exploitation patterns of fisheries resources.

Rebel Group Protection Rackets

Frances Duffy Kamil C. Klosek Luis Nardin Gerd Wagner | Published Wednesday, December 04, 2019System Narrative

How do rebel groups control territory and engage with the local economy during civil war? Charles Tilly’s seminal War and State Making as Organized Crime (1985) posits that the process of waging war and providing governance resembles that of a protection racket, in which aspiring governing groups will extort local populations in order to gain power, and civilians or businesses will pay in order to ensure their own protection. As civil war research increasingly probes the mechanisms that fuel local disputes and the origination of violence, we develop an agent-based simulation model to explore the economic relationship of rebel groups with local populations, using extortion racket interactions to explain the dynamics of rebel fighting, their impact on the economy, and the importance of their economic base of support. This analysis provides insights for understanding the causes and byproducts of rebel competition in present-day conflicts, such as the cases of South Sudan, Afghanistan, and Somalia.

Model Description

The model defines two object types: RebelGroup and Enterprise. A RebelGroup is a group that competes for power in a system of anarchy, in which there is effectively no government control. An Enterprise is a local civilian-level actor that conducts business in this environment, whose objective is to make a profit. In this system, a RebelGroup may choose to extort money from Enterprises in order to support its fighting efforts. It can extract payments from an Enterprise, which fears for its safety if it does not pay. This adds some amount of money to the RebelGroup’s resources, and they can return to extort the same Enterprise again. The RebelGroup can also choose to loot the Enterprise instead. This results in gaining all of the Enterprise wealth, but prompts the individual Enterprise to flee, or leave the model. This reduces the available pool of Enterprises available to the RebelGroup for extortion. Following these interactions the RebelGroup can choose to AllocateWealth, or pay its rebel fighters. Depending on the value of its available resources, it can add more rebels or expel some of those which it already has, changing its size. It can also choose to expand over new territory, or effectively increase its number of potential extorting Enterprises. As a response to these dynamics, an Enterprise can choose to Report expansion to another RebelGroup, which results in fighting between the two groups. This system shows how, faced with economic choices, RebelGroups and Enterprises make decisions in war that impact conflict and violence outcomes.

Policies to reconnect a city and the countryside

Tim Verwaart Gert Jan Hofstede | Published Monday, September 23, 2019The agent-based model captures the spatio-temporal institutional dynamics of the economy over the years at the level of a Dutch province. After 1945, Noord-Brabant in the Netherlands has been subject to an active program of economic development through the stimulation of pig husbandry. This has had far-reaching effects on its economy, landscape, and environment. The agents are households. The simulation is at institutional level, with typical stakeholder groups, lobbies, and political parties playing a role in determining policies that in turn determine economic, spatial and ecological outcomes. It allows to experiment with alternative scenarios based on two political dimensions: local versus global issues, and economic versus social responsibilitypriorities. The model shows very strong sensitivity to political context. It can serve as a reference model for other cases where “artificial institutional economics” is attempted.

Contract farming in the Mekong Delta's rice supply chain

Hung Nguyen | Published Tuesday, February 05, 2019We study three obstacles of the expansion of contract rice farming in the Mekong Delta (MKD) region. The failure of buyers in building trust-based relationship with small-holder farmers, unattractive offered prices from the contract farming scheme, and limited rice processing capacity have constrained contractors from participating in the large-scale paddy field program. We present an agent-based model to examine the viability of contract farming in the region from the contractor perspective.

The model focuses on financial incentives and trust, which affect the decision of relevant parties on whether to participate and honor a contract. The model is also designed in the context of the MKD’s rice supply chain with two contractors engaging in the contract rice farming scheme alongside an open market, in which both parties can renege on the agreement. We then evaluate the contractors’ performances with different combinations of scenarios related to the three obstacles.

Our results firstly show that a fully-equipped contractor who opportunistically exploits a relatively small proportion (less than 10%) of the contracted farmers in most instances can outperform spot market-based contractors in terms of average profit achieved for each crop. Secondly, a committed contractor who offers lower purchasing prices than the most typical rate can obtain better earnings per ton of rice as well as higher profit per crop. However, those contractors in both cases could not enlarge their contract farming scheme, since either farmers’ trust toward them decreases gradually or their offers are unable to compete with the benefits from a competitor or the spot market. Thirdly, the results are also in agreement with the existing literature that the contract farming scheme is not a cost-effective method for buyers with limited rice processing capacity, which is a common situation among the contractors in the MKD region.

Eliminating hepatitis C virus as a public health threat among HIV-positive men who have sex with men

Nick Scott Mark Stoove David P Wilson Olivia Keiser Carol El-Hayek Joseph Doyle Margaret Hellard | Published Wednesday, October 12, 2016 | Last modified Sunday, December 16, 2018We compare three model estimates for the time and treatment requirements to eliminate HCV among HIV-positive MSM in Victoria, Australia: a compartmental model; an ABM parametrized by surveillance data; and an ABM with a more heterogeneous population.

Social norms and the dominance of Low-doers

Antonio Franco | Published Wednesday, July 13, 2016 | Last modified Sunday, December 02, 2018The code for the paper “Social norms and the dominance of Low-doers”

How does knowledge infrastructure mobilization influence the safe operating space of regulated exploited ecosystems?

Jean-Denis Mathias | Published Tuesday, July 17, 2018Decision-makers often have to act before critical times to avoid the collapse of ecosystems using knowledge \textcolor{red}{that can be incomplete or biased}. Adaptive management may help managers tackle such issues. However, because the knowledge infrastructure required for adaptive management may be mobilized in several ways, we study the quality and the quantity of knowledge provided by this knowledge infrastructure. In order to analyze the influence of mobilized knowledge, we study how the following typology of knowledge and its use may impact the safe operating space of exploited ecosystems: 1) knowledge of the past based on a time series distorted by measurement errors; 2) knowledge of the current systems’ dynamics based on the representativeness of the decision-makers’ mental models of the exploited ecosystem; 3) knowledge of future events based on decision-makers’ likelihood estimates of extreme events based on modeling infrastructure (models and experts to interpret them) they have at their disposal. We consider different adaptive management strategies of a general regulated exploited ecosystem model and we characterize the robustness of these strategies to biased knowledge. Our results show that even with significant mobilized knowledge and optimal strategies, imperfect knowledge may still shrink the safe operating space of the system leading to the collapse of the system. However, and perhaps more interestingly, we also show that in some cases imperfect knowledge may unexpectedly increase the safe operating space by suggesting cautious strategies.

The code enables to calculate the safe operating spaces of different managers in the case of biased and unbiased knowledge.

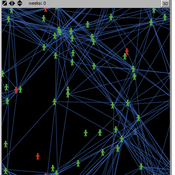

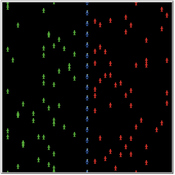

The Thin Blue Line Between Protesters and Their Counter-Protesters

Tamsin Lee | Published Monday, March 26, 2018More frequently protests are accompanied by an opposing group performing a counter protest. This phenomenon can increase tension such that police must try to keep the two groups separated. However, what is the best strategy for police? This paper uses a simple agent-based model to determine the best strategy for keeping the two groups separated. The ‘thin blue line’ varies in density (number of police), width and the keenness of police to approach protesters. Three different groups of protesters are modelled to mimic peaceful, average and volatile protests. In most cases, a few police forming a single-file ‘thin blue line’ separating the groups is very effective. However, when the protests are more volatile, it is more effective to have many police occupying a wide ‘thin blue line’, and police being keen to approach protesters. To the authors knowledge, this is the first paper to model protests and counter-protests.

Displaying 10 of 36 results for 'Blanca Rosa Cases Gutiérrez'